HOW TO USE NETWORK MAPS TO UNDERSTAND A CROWD

- ASHER NOVEK

- July 21, 2015

- 1:24 pm

“When crowds fill a public space they can change history,” observed Marc Smith, director of the Social Media Research Foundation, at Personal Democracy Forum this year. “And yet where are the pictures of the cyber crowd?”

We worry about our social networks—who’s following us, who are we following, how many likes am I getting, how many retweets did that get—but are we asking the right questions?

The Social Media Research Foundation’s project NodeXL displays maps of connections on Twitter in a unique way. By taking a topic or phrase and mapping out the connections in a network approach, we can see more than just who is talking to whom; we can see the communities that are being formed around particular issues. When we take a step back and see not just who the community is, but how it’s formed and what shape it takes, we can begin to ask deeper questions: Am I reaching who I want to reach? How can I reach that cluster of people over there? Do I want to reach that cluster of isolated people? The focus becomes less about numbers and more about the quality of the connections being made.

In the context of branding or marketing, there is obvious value to this: Am I growing my brand in the direction that it needs to? Am I getting my brand to the right communities, and which online leaders do I need to engage in order to do so? However, in the context of a social movement, the value is arguably more crucial. Social movements live and breathe online, but who analyzes the movement? Without the broad view of how a movement is shaped, it is left to grow or falter passively on its own.

NodeXL provides a tool for organizers and activists to see a movement, see who participated, and then see what kind of community has formed. Once you know what kind of community you have, you can look at ways to expand it, shape it, grow it, while mapping trends of the community over time. Collective action is difficult to cultivate and sustain; NodeXL provides a space to support action by asking questions like: Who are our main hubs? Which communities are talking about our issues, but not connected to the movement? How can we reach them? Do we have an active community or just a passive audience?

When answering these questions, we can streamline engagement processes and focus on the movement, not just the numbers.

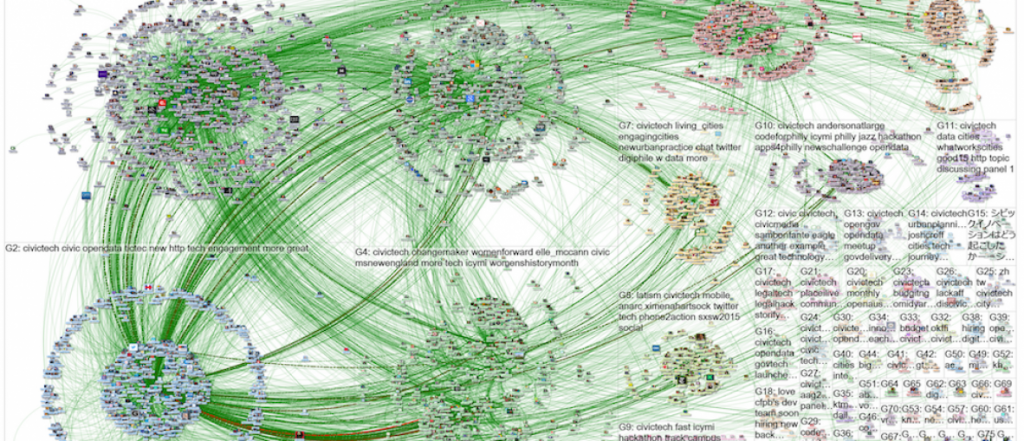

Here is an example of a NodeXL network map, comparing the community around “civictech” in May to the community in June. “As people reply and mention one another, they form links or ties that form communities,” Smith explained. “The civic tech network is predominantly a ‘hub-and-spoke’ pattern, with a hub that gets repeated (or retweeted) by many others. A large volume of completely disconnected people are a major portion of the population. These ‘isolates’ are mostly missing from these networks, but still contribute to the conversation. Some areas of the networks are ‘dense,’ which represents a community of connected people, without a central ‘hub,’ and many topic leaders.”

Overall, in May we see many hub-and-spoke clusters, such as the groups in G2, G5, and G6. This signifies audiences of people tweeting and retweeting from central groups of broadcasters, or mayors. But when we look at June, the clusters become denser. This signifies the audiences connecting to each other, rather than through central mayors, building a more dynamic community. We can also see clearer green lines (showing a direct connection) in May, and in June we see a more spread out series of lines, showing that more connections across communities were formed.

This change can largely be attributed to the Personal Democracy Forum being held, and is a good example of what a big, centralized event can do for a dispersed community, in terms of building relationships. Using NodeXL, we could see who became more connected to the community because of the conference, trace anyone who went from an isolate to a part of the community and vice versa. We can also see which new isolates entered the conversation, and over time with more comparative graphs, could see their growth in the community as well. This gives us the ability to know who to communicate with, and which “mayors” bring in more members of the community.

Having followers and retweets is important, but it’s only the surface level step. Numbers only get you so far, in order to understand how, why, and where you need to grow requires a network outlook. NodeXL, and the work Marc and the rest of the SMRF are doing, provides the tool to obtain and analyze that network.

Asher Novek is a freelance producer, storyteller, and community activist. He is the founder of HeartGov, an SMS based platform designed to connect local government and communities. HeartGov is currently running in Brooklyn, working with local elected officials and community based organizations to connect to citizens. Follow him @ashernovek.