EILEEN GUO ON SOCIAL MEDIA AND CIVIC TECH IN AFGHANISTAN

- JESSICA MCKENZIE

- August 31, 2022

- 6:02 pm

Eileen Guo is the founder of the digital media agency Impassion Afghanistan and the creator and curator of the Afghan Social Media Summit. Days before the third annual Afghan Social Media Summit (ASMS), Civicist chatted with Guo about the changing social media landscape, the first Afghan Social Media Awards, and the most exciting civic tech projects in Afghanistan.

What follows is a lightly edited transcript of our conversation.

Civicist: What was the impulse behind the first Afghan Social Media Summit? What were your goals?

Eileen Guo: When we started Impassion back in 2013, social media was starting to play a larger role in Afghan politics, culture, and daily life. It was kind of this undercurrent that everyone knew about, but it wasn’t really recognized publicly yet as the powerful force that it was (and would be). And with the 2014 presidential elections coming up, there was a lot of interest in bringing social media and tech to the forefront. A couple of things really happened at once that brought the social media summit to life: The international community in Afghanistan, especially the State Department, wanted to find a way to engage youth in the conversation as well as in civic engagement, and we, meanwhile, were really pushing to leverage social media as a tool.

So the State Dept. put out an RFP [Request for Proposal] to put together a social media summit as well as conduct provincial trainings and create a citizen journalism platform, and we responded and won the bid to conduct the summit and trainings. We ended up creating a citizen journalism platform anyway, because we saw the need for it, out of our own pocket. [Read Rebecca Chao’s techPresident piece on the citizen journalism platform Guo built here.]

Civicist: What were the biggest issues facing social media users in Afghanistan at the time?

EG: I think infrastructure and access have always been big issues—while ISPs and telecoms have been improving their services, internet in Afghanistan is notoriously spotty.

Other issues: a lack of basic awareness on privacy and cyber-security on both an individual and organizational level, a wariness as to the negatives of social media, cultural and generational resistance, censorship issues, etc.

Civicist: And these are all ongoing issues? What’s changed in the past few years?

EG: Well it’s interesting—I see the 2014 presidential elections as really the point where social media in Afghanistan came into its own. There was a very real concern as to social media’s potential for inciting violence during the elections dispute period. For example, I think the biggest changes have been in terms of infrastructure and access, which have improved a lot in the past few years—the government recently launched its own telecom with the aim of decreasing costs—as well as general awareness among the population of social media.

It’s fascinating though—even when you go into rural areas of Afghanistan, even those that might have never used these social networks themselves recognize the word “Facebook” because it’s so prevalent. It’s very much a part of Afghan culture now.

Civicist: What about the third annual ASMS are you most excited about?

EG: The first two years of the Afghan Social Media Summit were really proofs of concept, and this year it’s bigger than ever, 1,200 participants registered from 27 of 34 provinces, and also has better content and bigger-name speakers. It’s also the launch of something that I’ve personally dreamed of doing since we started Impassion Afghanistan, which are the Afghan Social Media Awards.

We started Impassion really with the goal of creating a sustainable self-driving ecosystem of Afghan internet users, and everything that we’ve done since—creating the largest citizen journalism platform in the country, Paiwandgah; running the Afghan Social Media Summit; teaching basic-level social media workshops in hard-to-access provinces—all of this helps drive towards that goal.

The Afghan Social Media Awards, which this year will be giving out awards in ten categories and will be broadcast on national TV, provides an incentive for individuals and organizations to strive to improve their social media use, while also teaching attendees and viewers about what makes for “good” social media use.

Civicist: When we spoke previously, you said that technology is one of the few, if not the only, sectors still growing and doing well in Afghanistan—what about civic tech? Are there any exciting and positive community- or government-driven tech projects for the public good?

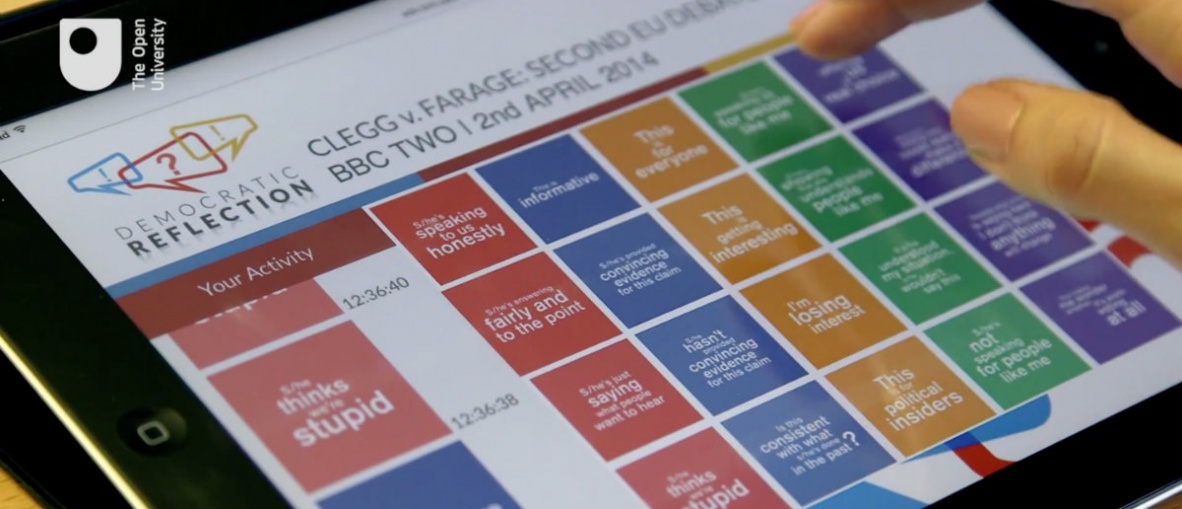

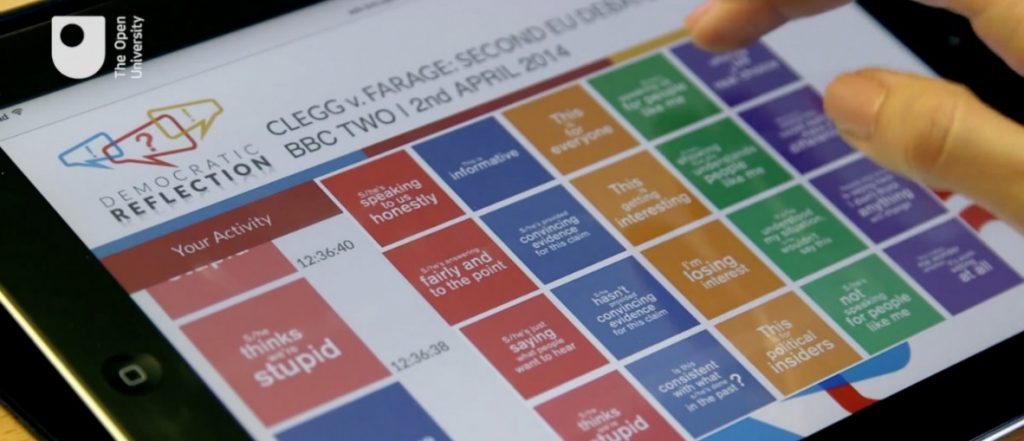

EG: Yes, definitely, and that’s actually a key focus of the summit. For example, TOLO, the country’s largest television station, will be launching their civic media project at our event, a government accountability project with both TV and web tie-in’s. The TOLO project is currently in beta and will only launch officially in a few days. It’s based on/inspired by SadRoz.af, the platform that we created to monitor the first 100 days of the presidency. (You can see the similarities throughout.)

But more generally, there is a lot of interest in using technology for citizen-government relations, both within the government itself (President Ashraf Ghani is a big supporter of tech and actually ran a social media campaign back in 2009 during his first campaign for the presidency) as well as via the international donor community.

Civicist: Anything else you’d like to add?

EG: Afghans are a very proud people—and rightfully so. What’s really exciting to me about technology and social media in Afghanistan is that it is an area where Afghans are legitimately right to be proud. The amount of progress that’s been made in a decade is very exciting, and it’s gotten to the point where it’s not even fair to say simply that Afghanistan has leap-frogged in terms of tech adoption—in some cases it’s actually leading the way regionally, and this is a focus of this year’s event as well.

Civicist: Anything in particular you want to point to as a source of pride?

EG: That the 3G network came to Afghanistan before Pakistan [in 2012; Pakistan got it in 2014] is a huge point of pride. And (to a smaller scale and to a more specific audience) [the fact] that initiatives like CodeWeekend, Hour of Code, Founder’s Institute, etc. are starting to gain popularity.

Relatedly, technology is an area where Afghans, especially young Afghans, really feel connected to the global community. Not only in that Afghans are now able to connect to others around the world on Facebook or YouTube (which is of course huge), but that Afghanistan is playing a role on the world stage in terms of tech.

So I guess what I’m really trying to get across is that Afghan internet users—as well as internet users in “developing countries”—are a force to be reckoned with, and internet companies, policy-makers, etc, should take note. They’re only starting to realize their own power, but it’s a large population that is coming online for the first time, but as they continue to do so and their numbers grow, the companies/service providers/policy makers that can cater to them are going to benefit.

Civicist: What do you think the impact of these new users will be on the internet?

EG: I love that question! And that’s another [topic] we’ll be discussing at the event.

Afghan users understand and use the internet and social media slightly differently from in other parts of the world due to cultural, economic, and historical context. For example: while the actual percentage of social media users is low, the offline-online linkages mean that the actual reach is much higher, because when a text message (from a presidential campaign, as has happened) comes in, a family or mosque or other community will have it read out loud. And so how do advertisers create messages that take into account this kind of context? That’s a question that our agency is working on.

Or how do we leverage the amount of offline blue-tooth social sharing, which has created kind of an underground social network? Or redesign popular web and mobile apps for illiterate populations?

I mean, one of my best female friends in Afghanistan is illiterate, and yet we communicate regularly on WhatsApp and Skype. It’s incredible how much she’s managed to learn to use these services without knowing how to read, but what if we were to design apps that are specifically aimed at people like her?

Civicist: Absolutely! This is great, thank you for taking the time to chat, Eileen.

Full disclosure: Micah Sifry wrote a letter of support for Guo’s Afghan Social Media Summit proposal.