MAKING THE UK’S POLITICAL DEBATES MORE RESPONSIVE TO PUBLIC NEEDS

- CHRISTINE CUPAIUOLO

- February 8, 2016

- 4:14 pm

====================

Case Study: Election Debate Visualization Project

Country: United Kingdom

Research Team: University of Leeds: Stephen Coleman, Giles Moss (School of Media and Communication), Paul Wilson (School of Design); the Open University’s Knowledge Media Institute: Anna De Liddo, Brian Plüss, Alberto Ardito, Simon Buckingham Shum (now at the University of Technology Sydney)

Debate: ITV Leaders Debate, April 2, 2015—the only debate where all seven leaders of British political parties met in advance of the May 7 general election for the 56th Parliament of the United Kingdom.

====================

Picture this: You’re watching a televised debate involving two political candidates, and one of them accuses the other of breaking a campaign promise. There’s a denial, followed by a cross-accusation. Pretty soon you’re not sure if either candidate is telling the truth, but you are certain that they’re avoiding the central question, and the moderator seems unable to refocus the conversation.

Now, what if you could replay the debate—but this time, there’s built-in fact-checking and data maps that track the arguments and show who violated the debate rules? And what if the viewing platform was interactive, so you could call up previous articles about an issue, pull in other viewers’ responses to the debate, and share your own?

What if, in other words, debates became more informative after the debate? Could the enhancements increase viewer comprehension, engagement, and political confidence?

That’s the question researchers working in Britain on the Election Debate Visualization (EDV) project are attempting to answer.

Robust political debate is common in the United Kingdom; the weekly Prime Minister’s Questions has been broadcast live since 1990, drawing international audiences. The first televised election debates, however, didn’t take place until 2010. They attracted strong public interest, but through a series of national surveys completed before and after the debates, Stephen Coleman, a professor of political communication at the University of Leeds, found that many viewers were left with questions on the issues and uncertainty about the candidates’ competing responses.

In 2013, researchers from University of Leeds, including Coleman, teamed up with data science experts at the Open University’s Knowledge Media Institute (KMI), a research and development lab, on the EDV project. The three-year effort (it concludes this fall) aims to identify the information needs of various audiences and create interactive visualization tools that respond to those needs.

“The analogy that I often use is that the debate is rather like trying to buy a car from someone who is a very fast-talking salesperson,” said Coleman. “What we want to do is to give you a chance to go home, sit at your computer, slow the whole thing down, take it apart, and really ask the questions that you want to ask.”

KMI researchers had already been conducting some informal experiments around creating interactive maps that tracked argumentative moves during the 2010 prime-ministerial debates. They were eager to do more with debate rhetoric and computer-supported argument visualization (CSAV), which captures and presents argument structure. They also wanted to analyze “fair play,” a specialty of EDV team member Brian Plüss, a research associate at KMI who codes linguistic behavior. Also known as non-cooperative dialogue, fair play refers to how well a candidate sticks to the debate rules. Avoiding a question or interrupting another candidate would be considered violations.

With a grant from the Engineering & Physical Sciences Research Council, the EDV team set out to develop an open-source web platform that would allow viewers to re-watch a debate with a full array of interactive visuals and analytics on discourse, audience feedback, debate topics (such as healthcare or the economy), and, in the future, data-mining tools that could answer such questions as, “Did the candidate actually promise this last year?” They named it Democratic Replay and expect to release in May, with a tutorial explaining the components.

But that’s not the only interactive use of technology they are introducing to the debate experience. Early on in the collaboration process, as ideas were being tossed around, the project team decided to see if they also could create an audience-response web app that would provide genuine insight into voters’ attitudes and needs. It was outside the project scope (and unfunded), but they were motivated by voters wanting a say in the debates and the limitations of existing ways to capture feedback.

In 2010, for instance, U.K. debate broadcasters introduced the “worm,” an analytic tool used to gauge audience responses. Using a control device, such as a dial, a pre-selected group of voters register approval or disapproval of the candidates’ comments, and the responses appear in a line graph on screen, wiggling like a snake or a worm. Some researchers have had concerns about the tool’s influence on debate viewers.

“We agree with the view of the House of Lords Select Committee on Communications that ‘the use of the worm might distort the viewer’s perception of the debate,’” EDV team members wrote in a 2014 project report, referring both to the small sample of participants and the fact that the worm only asks the audience to “like” or “don’t like” what the candidates are saying. There’s no context.

More insight into voter reactions can be gained by analyzing Twitter activity during the debates, but this, too, is limited. “If instant audience feedback is to be a new fact of political life,” they concluded, “we need better tools for capturing and interpreting what viewers and voters are thinking.”

Gathering Debate Reactions

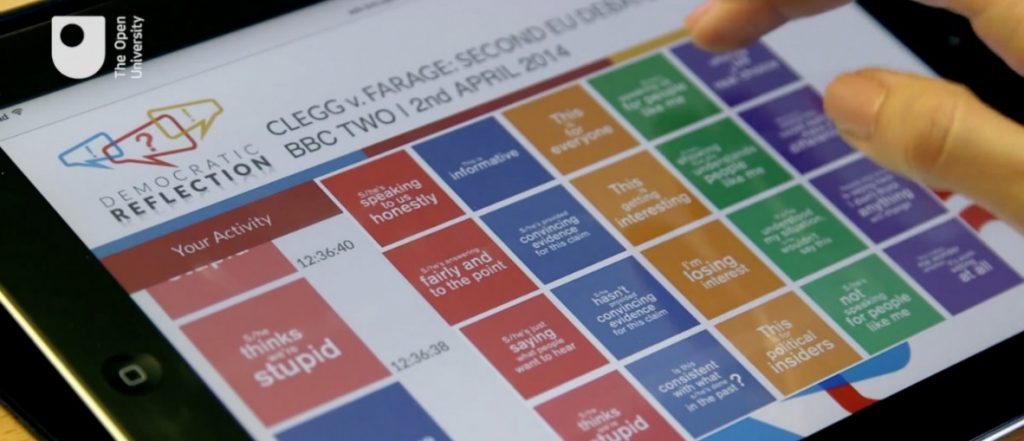

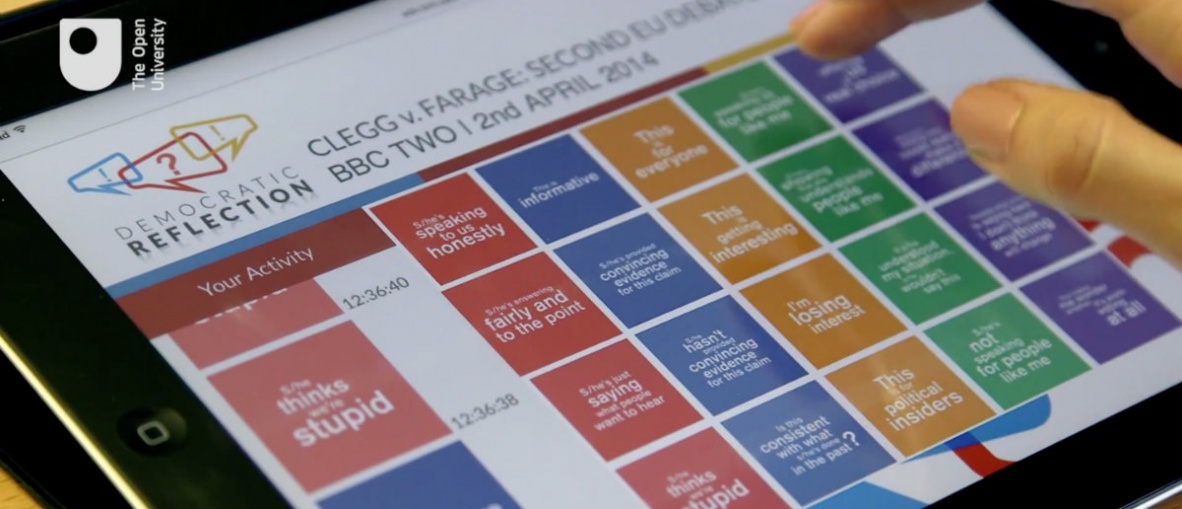

The audience-response app—called Democratic Reflection—began as a paper prototype. EDV team member Anna De Liddo, a research fellow at KMI and leader of the Collective Intelligence and Online Deliberation group, proposed using flashcards to elicit more nuanced feedback.

The team settled on 18 cards representing three categories: emotion (how debate viewers related emotionally with what they were viewing), trust (whether viewers trusted the person speaking or what was being said), and information need (if viewers had questions about the debate topics).

Collective intelligence systems generally require complex tasks to be broken down into smaller tasks, with the actions distributed across large collectives. Looking at how this could be applied to political debates, De Liddo focused on this question: “How can we capture and harvest people’s feedback to the debate in a way that is light and non-intrusive enough so that people may be willing to react, but also in a way that is nuanced and detailed enough so that analysts can make sense of the feedback?”

The flashcards were designed to gather “soft feedback,” meaning that viewers voluntarily share what they are thinking or feeling. There are no intrusions, and no binary questions such as, “Do you agree or disagree with the candidate’s response?” This type of collective intelligence can be useful for analyzing both the viewer’s immediate experience and shifts over time.

On April 2, 2014, the team invited 15 students from the University of Leeds to demo the cards during a one-hour televised debate between Nick Clegg, then-deputy prime minister, and Nigel Farage, leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party, on whether the UK should remain in the European Union. The BBC hosted the debate in front of a live audience.

Participants were encouraged to raise a card in the air at any time if it represented how they were feeling. The experiment was recorded so researchers could later code each response. They used Compendium, a software tool for mapping information, ideas and arguments with support for synchronized video annotation.

Plüss said the team initially thought the cards offered too many options. Debates can be complicated enough to follow without the added responsibility of choosing from 18 different reflections. To their surprise, the students not only engaged with the cards throughout the entire debate (researchers cataloged 1,472 times the cards were raised), they even started to combine several cards together to express more complex feelings.

When Plüss reviewed the video, he also realized the students started selecting the cards based on design elements. “That gave us a lot of courage because we thought if they engaged with these pieces of paper like that, then maybe if we give them an app, it’s going to be even easier,” he said.

Determining Democratic Entitlements

Around the same time the flashcards were being developed and tested, Coleman, along with two other University of Leeds researchers (Giles Moss, a lecturer in media policy, and Jennifer Carlberg, a doctoral candidate), asked groups of voters and non-voters about their experience with the 2010 televised debates and what they hoped to gain from future debates.

The Leeds team identified five demands, or “entitlements,” that people said the debates needed to fulfill in order for them to feel comfortable taking part in the democratic process:

- They wanted to be addressed as if they were rational and independent decision-makers.

- They wanted to be able to evaluate the claims made by debaters in order to make an informed voting decision.

- They wanted to feel that they were in some way involved in the debate and spoken to by the debaters.

- They wanted to be recognized by the leaders who claimed to speak for (represent) them.

- They wanted to be able to make a difference to what happens in the political world.

The design of the focus groups was ambitious. Researchers looked at the relevance of debates in the broadest sense; that is, not whether the debates simply influenced viewers’ perceptions of the candidates, but what people need in the run-up to and during the debates to propel them to engage. (The interviews are also discussed in this report). This moved the focus from the politicians (suppliers of information) to the public (demanding information).

Why go to such trouble?

“We were looking at this on the basis that Britain claims to be, as the United States claims to be, a democracy. In a democracy, you have a public which is in charge and which makes the most important decisions about its future,” said Coleman.

“Very often when political scientists talk about the public, what they say is, ‘Oh, people can’t understand that,’ or, ‘This is too confusing for people.’ That wasn’t really good enough for us. We wanted to know the answer to the question, ‘What is it that makes this confusing?’ Is it inherently the case that the electorate is just dumb? Probably not. If not, then there are barriers in the way. If there are barriers in the way, what are those barriers? Are they barriers that are the same for everyone, or are they different for some people? Are they movable?”

Coleman said getting to that point was made possible by the decision to go into the focus groups with a curiosity about what norms people would establish for themselves, instead of establishing a set of norms for them to meet. Besides being surprised about how forthcoming people were about what they needed to make democracy work for them, and how much people wanted the debates to involve them as well as inform them, the researchers were a little startled by the lack of interest in digital technology as a solution.

“There’s an assumption that people are looking to digital technologies. They weren’t looking,” said Coleman. “They’re looking for particular opportunities to do things rather than particular technologies that they think have got a magic solution.”

Focus group participants came up with interesting ideas for improving the debates, said Plüss, including penalties for candidates who dodge questions. While such a suggestion would never pass the negotiation stage—much like it is with debates in the United States, the debate format in the United Kingdom is decided after a long negotiation between the political parties and the broadcasters—the EDV team began to envision how technology could be used to deliver more of what the public wants.

“If one of the politicians says something that has no evidential basis or that is plainly wrong, we can show it, and then make people aware of that,” said Plüss. “Even though we can’t make changes to the debates themselves, with technology we can empower citizens. That’s one of the overall grand goals of the project.”

From Flashcards to Web App

It took almost a year to turn the Democratic Reflection flashcards into a web-based app. The digital design ended up being similar, but the statements were restructured to extract meaningful insights around the entitlements identified in the focus groups. Coleman recalled arguments over Skype, debating whether to make the questions more colloquial, for example, or the options easier to analyze.

The choices now range from straightforward (“This is informative” / “I’m losing interest”) to more complex reflections (“If s/he understood my situation, s/he wouldn’t say this” / “S/he’s provided convincing evidence for this claim”).

“People’s reactions are used to make sense and assess the debate, but from a people-perspective,” said De Liddo, adding that this collective point of view “would be impossible to capture otherwise in such a rich way and, most importantly, in a way that provides very specific insights on the democratic entitlements.”

“Additionally, people who did not watch the debate can eventually ‘replay’ people’s reactions, and these can also be part of how they shape their opinion on the debate,” she added.

In March 2015, researchers assembled a dozen Open University students and staff in an auditorium to watch the Clegg/Farage debate from a year ago. This time, instead of holding up flashcards, participants could open the Democratic Reflection app on their laptops, tablets, or smartphones and select from 20 color-coded reaction buttons. A second test that month was similarly structured, except participants from the University of Leeds watched the debate independently (on YouTube), at home or at work, to better simulate a real-world scenario.

Everything worked as expected. But all of these tests involved university students or staff, so the users were generally tech-savvy, and no consideration was given to their age, gender, or political leanings. There wasn’t money in the budget to repeatedly test the app with a demographically representative sample of voters.

For that, the EDV team would have to wait until the main event—the ITV Leaders Debate on April 2, 2015—a year to the day of the original flashcard test.

One Test Becomes Two

In advance of the Leaders Debate, the EDV team turned to a polling company to recruit more than 300 people to use the Democratic Reflection app. Participants were given a pre-debate survey about their views on the election and a post-debate survey about the event and their experience using the app. At the end of it all, the team gathered data from 242 participants; some didn’t watch all of the debate, or didn’t complete both surveys.

Plüss said most users were active for the full two hours, with activity peaking near the end, during closing statements. The EDV team was concerned 20 buttons would making viewing more complicated, but that didn’t seem to be an issue.

“It leaves the question open to see how many [statements] people would be able to take,” said Plüss, adding that some users indicated that they would have liked more options, particularly more emotionally charged responses—the impolite things people say when they’re watching a debate and something happens that makes them yell at the TV.

On April 16, during a BBC election debate featuring the leaders of the five main opposition parties, the EDV team made the app available to everyone.

It wasn’t planned as part of the study, and they did very little promotion, only a couple of tweets and a mention on the Open University’s Facebook page. The server was optimized to support up to 700 users, said Plüss, and that night, as he watched the number of logins inching upward, he grew anxious. Close to 2,000 people joined in. Sure enough, the server crashed.

“Obviously, if we had collected that amount of data without any interruptions, it would have been amazing, but the fact that we got that amount of interest, I think it’s wonderful,” said Plüss. “It’s not that people were just coming in, taking a look, and leaving—they were actually wanting to interact.”

In fact, that interaction is probably what caused the crash. The team had modified the platform, allowing users to view a live feed of other viewers’ reflections as well as their own responses.

“The idea was to create a bit of a more of a social community kind of experience,” said Plüss. “Technically, that’s what got us in trouble, because that stream of information, when you have such a high number of users, is huge.”

The server was down for about five minutes. But Plüss considers the extra run a success of sorts: To his surprise, some users returned, and the EDV team ended up with about 400 streams of data—not useful for longitudinal data, due to the gap in the middle, but researchers could still study responses to specific moments of the debate.

Besides harnessing more data, said Plüss, “It was amazing to see that people had the appetite for this concept.”

The EDV team is open to discussions with media partners in and outside Britain interested in using the Democratic Reflection app in future debates. The entitlements on which the questions are based might be different, and the technology might be applied in different ways, but the ultimate goal of providing debate viewers with the means to express their emotions as well as their needs could be applied in any country, said Coleman.

“When we were doing this in April and May of 2015, we were saying to each other, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we could do something for the presidential election in the States in 2016?’ My guess is it is almost certainly too late for that,” said Coleman, adding that Germany’s election in 2017 might be a more realistic possibility.

“What we’re looking at is who we can work with for the greatest public good,” he added.

Launching Democratic Replay

Democratic Replay will be made public in May as a tutorial website. It will include an analysis of data gathered from the Democratic Reflection app—51,964 pieces of data to be exact, one for each time a viewer clicked on a reflection during the ITV Leaders Debate on April 2.

The EDV team is working on multiple layouts with programmer Alberto Ardito, a visiting research student from the Polytechnic University of Bari in Italy. One shows a timeline of audience responses; click anywhere on the timeline to bring up that point in the debate. Another option shows a histogram as the video plays. There’s also a “feedback flower,” its size corresponding to how many people chose a particular reflection during each 10-second segment.

“What our analysis will show is what was going on during the debate when people felt that particular entitlements were either being satisfied or being particularly not satisfied,” said Coleman.

Users will be able to filter the demographic profiles of viewers who provided feedback, making it possible to compare, say, how men and women responded to a candidate’s statement. Argument maps, fact-checking, and other components will also be available.

The EDV team finished the first iteration of Democratic Replay in October, five months after the election—too late to test if the platform could affect civic engagement or influence voting behavior. But between May and the end of the EDV project in September 2016, the team will continue to assess its use.

In the future, it might be possible to produce a Democratic Replay within a week of a debate, said Plüss. That’s well outside the 24-hours news cycle, but the team thinks the value is in turning the debate into an educational resource and a hub of data for journalists and other researchers.

As for the general public, the platform is going to be most useful for those who watched the debate, said Coleman. Both technologies, Democratic Replay and Democratic Reflection, are aimed at people who are “taking some notice of what’s going on,” but who may not have followed everything closely or who have not yet decided who to vote for.

“What I don’t think Democratic Replay as a technology does is open up a lot of space for people who are completely disengaged from the process,” said Coleman. “I think that will involve us in a different piece of work.

“It can be done, but I think that the problem is to throw everything in and try to take the disengaged, the engaged-but-confused, and then the engaged-but-highly opinionated all together and assume that you can create technologies for all of them. You can’t, I think.”

After all, this isn’t the worm.

University of Leeds researchers concluded that the

University of Leeds researchers concluded that the