WHAT ANTI-CORRUPTION WORK LOOKS LIKE IN RURAL NEPAL

- EILÍS O'NEILL

- December 5, 2015

- 3:20 pm

The money was supposed to buy bicycles for ten girls attending public school in Mahottari, Nepal. The head of the village government allocated 150,000 rupees—about $1,400—for the project, which he said would encourage girls from the marginalized Dalit (so-called “untouchable”) community to attend school. An auditor signed the paperwork and the money left the government’s coffers.

“Not a single student in the village got a bicycle,” says Pranav Budhathoki, the founder and CEO of the Local Interventions Group. Budhathoki received an anonymous report of the missing funds during the pilot of an anti-corruption project he is looking to launch throughout the country of Nepal. He immediately sent his regional representative, a respected journalist in Mahottari, to find out what happened to the money.

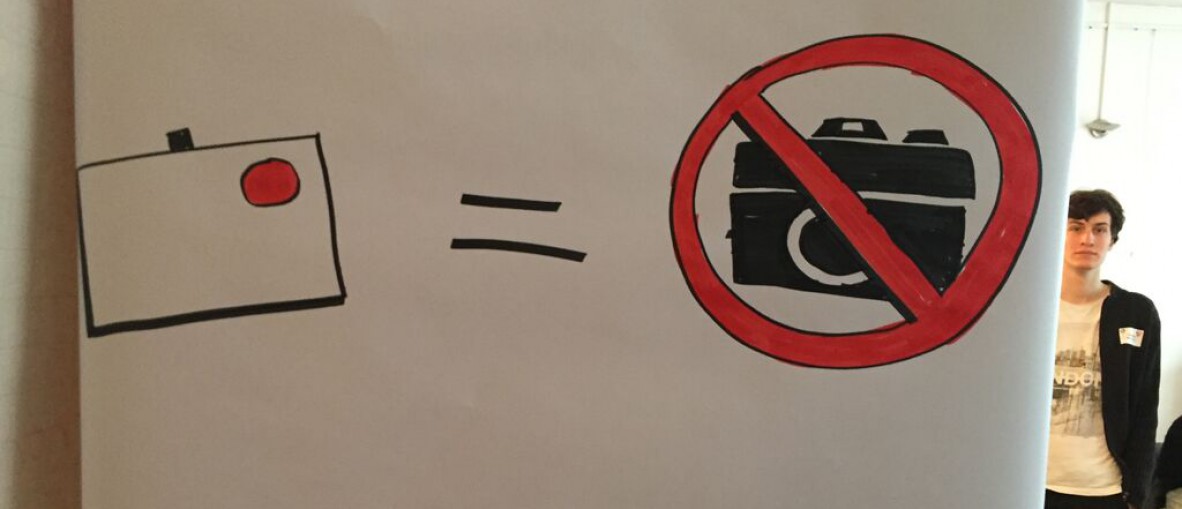

Budhathoki is trying to curb corruption in Nepal by publishing information about local government budgets—about where money should have gone—and then eliciting feedback from citizens about what projects actually happened. In urban, wealthy contexts, people can use smartphones and apps to crowdsource information about corruption, but Budhathoki knew that wouldn’t work in rural, undeveloped parts of Nepal. So he came up with an alternative: People could submit reports of corruption using very simple tools—text messages and phone calls—and he would use technology on the back end to aggregate, analyze, and publish the data. This is the key to development, he says: not to increase funding or develop new projects, but rather to give citizens the information and the tools they need to demand accountability.

“The problem is not resources,” he explains. “The problem is citizens not knowing how much the government has allocated in their name.” To solve the problem of corruption, he says, it’s necessary for people to be “engaged and involved and reporting what they see around them, the malpractices and corruption issues.”

According to Budhathoki, the Nepali government sends money to Village Development Committees to address every imaginable social injustice, but “up to 60 percent of that allocated budget gets sent back to national coffers because the local governments don’t spend it,” he says. Local news reports corroborate that claim. As a result, Budhathoki says, “health centers are running without medicines and doctors, and kids are attending schools with no books or teachers.”

Budhathoki founded the Local Interventions Group in September 2011. Since then, he’s launched an app aimed at reducing police abuses and increasing police effectiveness and has used the open-source software Ushahidi to address cheating and violence in the 2013 Nepali elections and to ensure that earthquake relief services and supplies reached the right people after this year’s earthquake. His newest project tackles corruption head-on by publishing information about budgets and then crowdsourcing reports of corruption. He ran a pilot project last year in two of Nepal’s 75 districts, and, over the next two years, he plans to scale up the program so it will reach the entire country.

Here’s how it works: First, the Local Interventions Group’s regional representatives, all well-connected reporters, ask government officials how much money was earmarked for, say, schools or clinics in a certain area. Then, the Local Interventions Group crowdsources reports about what is needed, what is being done, and the quality of the work.

During a three-month pilot, Budhathoki solicited reports in each of three categories: absenteeism of local officials, misspent or disappeared development funds, and missing pension payments. At “Mobile Help Desks,” volunteers gathered information from text messages and phone calls. Budhathoki received 1,300 citizen reports. Then, the regional representatives verify the reports with local government officials and threaten to make the information public unless the grievance is resolved. Over the course of the three months, the Local Interventions Group verified about 600 to 700 genuine, specific, and actionable reports.

Take the bikes for female students, for example. Budhathoki’s contact in Mahottari took the report of the stolen bicycle funds to the district government. “Within three days, he got a call from the chief district official,” Budhathoki says. The Village Development Committee secretary admitted responsibility and promised to return the money. It took three more months, but “the 150,000 rupees was finally returned back to the national coffers,” Budhathoki says. No girls have gotten bicycles, since there’s a new government with new priorities in office, but the money is back where it belongs.

As Budhathoki scales up his anti-corruption project to the entire country of Nepal, he hopes to streamline his interactions with the government. His NGO will collect, vet, and verify grievances; map them onto a GIS platform; and then share the reports both with government officials and civil society organizations. That way, “each district official, head of the village government, [will] see these reports at his desk, on his computer, early morning every day so that he can talk to his colleagues on the ground and do something about that,” Budhathoki says.

Several researchers who have investigated anti-corruption programs say such collaboration is the key to success. Carla Miller is the founder and president of City Ethics, a nonprofit that aims to help local governments develop programs to prevent corruption, and has prosecuted federal corruption cases involving elected officials. She’s found that anti-corruption programs entirely internal to the government with no line to citizens can themselves be corrupted, while citizen groups can lose momentum and don’t necessarily understand the inner workings of government. “Ultimately, you have to have communication, collaboration,” she says.

The spirit of collaboration with government officials was behind Budhathoki’s decision to take down a map of crowdsourced corruption reports he’d initially published on the Local Interventions Group’s website. “We put it up for a month and then we shut it down because the government was getting antsy because they didn’t want citizens to know there’s a lot of corruption in the government agencies,” Budhathoki says. “Of course everyone knows that there’s a lot of corruption in government agencies at the local level but they didn’t want that to be up on the website for everyone to see.”

So, in the end, Budhathoki came to the conclusion that taking the map down was the right decision. “We’re okay with that because my approach has been collaborating with government officials rather than confronting them,” he says—and, now, he adds, he can walk into government offices and say, “Alright, let’s try to change something on the ground.”

This is a controversial approach. Some analysts, such as Miller, agree that taking down the map was the right call. “Maps of corruption and press and then a reaction from the government” is just a short-term solution, she says, that “doesn’t integrate citizens into long-term planning and identifying those issues faster.”

Yuen Yuen Ang, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Michigan, has looked at the platform I Paid A Bribe, which crowdsources reports of corruption in India, and similar platforms in order to identify what works and what doesn’t. She agrees that working with the government should be Budhathoki’s priority.

“Budhathoki made a pragmatic choice in agreeing to the government’s request—which, importantly, was a request, not a demand,” she wrote in an email. “By doing so, he avoids antagonizing the government, making it more likely for state authorities to work with his organization to take concrete steps in fighting petty corruption.”

“The purpose [of crowd-sourcing initiatives] is not to shame the government or individual officials, because, as Budhathoki himself points out, everybody already knows there is a lot of corruption,” she adds.

The Local Interventions Group isn’t combating corruption within elite circles, which Ang says would call for a political response, but rather what Ang refers to as “petty corruption”—that is, “low-stakes, diffused corruption that directly affects the lives of regular citizens.” Changing out government officials has no effect on small-scale corruption, Ang says, since it’s a systemic problem. Instead, the best way to approach the problem is through procedural changes: for example, “reducing bureaucratic discretion, centralizing budgetary management, reforming public compensation practices, etc.”

Budhathoki was able to make such a collaborative procedural change when it came to paying pensions. During his pilot, he found many people didn’t get their pensions on time, or at all. The government officials decided that, when the next month of pension payments came due, they’d have the Local Interventions Group’s regional representatives oversee the process, verifying who was owed a pension and who received one. That way, “we know how much money is being given to whom,” Budhathoki says. “The whole process [is] transparent.”

That’s the kind of change he hopes to continue to make in the future. “That happened because we’re seen as partners,” he concludes.