Parsing Upworthy’s Big Pivot

- DAVE KARPF

- July 9, 2015

- 7:39 pm

Equating Upworthy with clickbait has always obscured the real secret to their success: the company is among the web’s most deft practitioners of sophisticated analytics.

Since launching in 2012, Upworthy has done a few things very well.

Upworthy perfected the socially-optimized “curiosity gap” headline. This was both a blessing and a curse—the site attracts around 20 million unique visitors per month, but it is synonymous with clickbait, an image they haven’t quite been able to shake even after shifting away from those thoroughly unloved headlines.

Upworthy mastered curating the web—finding high-quality content with bad headlines, then tinkering with the framing to give it better headlines and help it find an audience. That has been Upworthy’s niche for the past three years. But that’s changed now that Amy O’Leary, formerly of the New York Times, has taken the helm as Editorial Director. Now, Upworthy is producing its own 5,000 word articles about the fast food industry. Its staffers are called “editors” instead of “curators.” This week, O’Leary released a new report on “Upworthy’s Editorial Vision,” which helps to define this pivot in Upworthy’s content strategy.

As the company transitions to content creation, it’s worth asking what makes Upworthy different. Equating Upworthy with clickbait has always obscured the real secret to their success.

It isn’t the clickbait headlines. Plenty of imitators picked up on Upworthy’s rhetorical stylings, leading Peter Koechley to announce “sorry we kind of broke the internet last year” at The Guardian’s 2015 Changing Media Summit. In fact, Upworthy has been moving away from “you won’t believe what happened next”-style headlines for years. They started using those headlines because they tested well. Then everyone else started using the same headlines. Then users got tired of them. So they didn’t test so well anymore, and Upworthy’s style shifted.

In fact, “clickbait” doesn’t do justice to Upworthy’s viral model. The point of Upworthy was never to maximize clicks. It was to maximize shares. If people click on a headline and are disappointed with what they find, they generate a single page-view. (That’s nice if you have an advertising-based business model. Upworthy doesn’t, and never has). If people click on the headline and like what they find, then they’re more likely to share that piece of content through Facebook and Twitter. And that’s how the audience grows and progressive messages break out of their Filter Bubbles.

It isn’t Facebook optimization. Facebook is the main driver of online news traffic today. Companies used to focus on “search engine optimization,” reasoning that the way people find anything new online is through google searches. Today, companies focus more on social optimization, recognizing that the balance of online power has shifted. But Facebook can be a cruel master. Tweaks to the Facebook algorithm can send your traffic plummeting. If you are too successful at generating traffic through Facebook, the site might just decide to duplicate your model and bring that traffic in-house.

It isn’t the content itself. Part of what has made Upworthy different from its copycats is the focus on substantive content with a progressive bent. Upworthy, so to speak, is people. Hiring the right curators with the right taste and judgment has been a core element of finding and shepherding share-worthy social content. But that content has always come from mining the web. All of Upworthy’s top hits have come from some other media producer.

No, what makes Upworthy special is their approach to analytics. Tracking the right data, thinking about data, and using data correctly has always been the thing they get more right than anyone else.

Analytics was at the core of their initial launch. Eli Pariser and his team realized that simple A/B headline testing (the same type of testing that he’d done for years as Executive Director of MoveOn) could help build a massive audience for important stories that simply had never been framed right.

Analytics was what drove them to clickbait. (Except it was actually sharebait.)

And then analytics was what drove them away from clickbait. In February 2014, Upworthy stopped focusing on pageviews and unique visitors and started focusing on “attention minutes.”

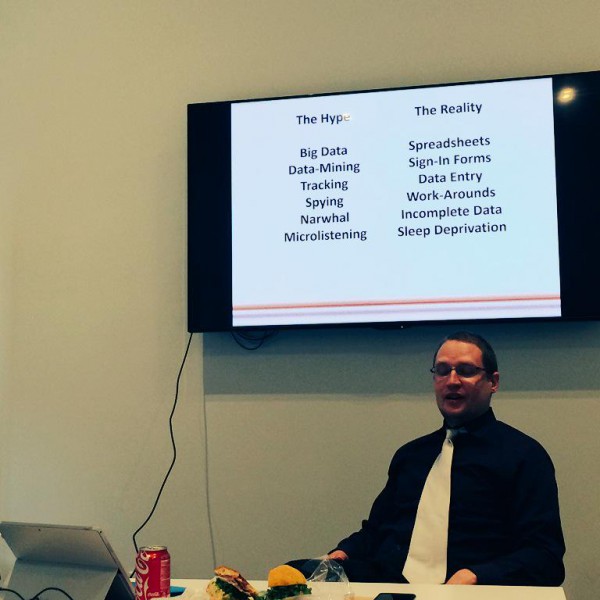

The switch from pageviews to attention minutes is emblematic of what sets Upworthy apart from its competitors. Everyone uses some form of analytics these days. It’s relatively simple to measure pageviews, clicks, retweets, and shares. Analytics is basically how we keep score in modern-day journalism.

But all this digital data can easily lead you astray, particularly if you’re measuring the wrong thing. Optimizing for pageviews leads to a bunch of stupid slideshows. Optimizing for clicks leads to curiosity-gap headlines, regardless of the story they link to. Optimizing for fundraising leads to an endless string of dire warnings.

Take a look at slides 17-20 in O’Leary’s slide deck. Upworthy has spent a year and a half gathering rich data on attention minutes from tens of millions of visitors. That’s data they have and their copycats don’t. And now they’re starting to use that data for their own storytelling. Whatever happens next, they’ll monitor, listen, and learn, and adapt.

The hard part of the new digital journalism isn’t the math or the software code that drives analytics and A/B testing. The hard part is figuring out what the right metrics are. Focus on the easy stuff and you’ll create a powerful engine driving you inevitably towards irrelevance. The center of Upworthy’s big pivot is a focus on the hard parts of analytics. That focus drove them to be the social web’s biggest curators. Now it will drive them as the social web’s latest content creators.