THE IMPORTANCE OF OPEN DATA TO 21ST CENTURY REGULATION

- MARK HEADD

- December 16, 2015

- 2:56 pm

In the absence of open data standards, companies like Airbnb can define their own terms for behaving in an “open and transparent” way.

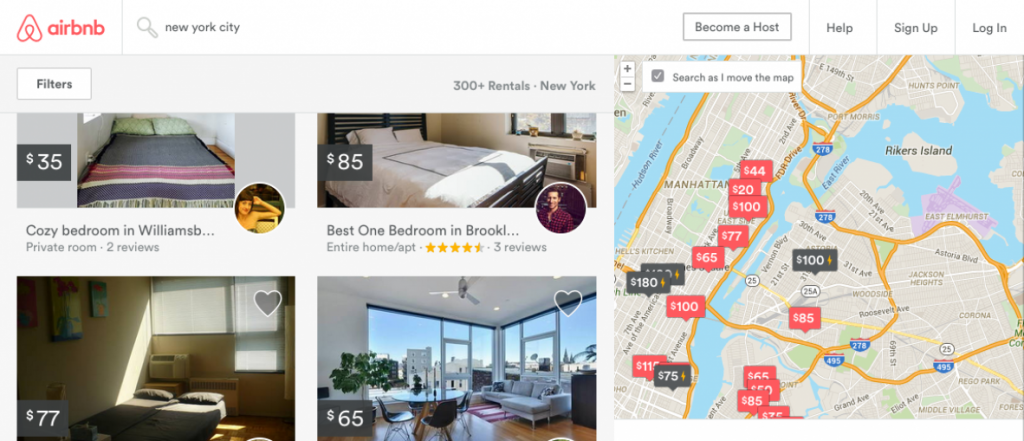

In early December, Airbnb made headlines by releasing some data on how people are using the company’s platform in New York City.

In doing so, the company has provided an object lesson in the critical role that data plays (and will continue to play) in government regulation of private companies in the 21st century, and highlighted how ill-equipped governments are to obtain and use this data.

AIRBNB AND THE STATE

Over the past year, the use of Airbnb to rent properties in New York has received intense scrutiny from government regulators because of suspicion that a non-trivial amount of rentals listed on the site were in violation of state or city rules. In late 2014, New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman released a report examining Airbnb rentals in New York that concluded that “most short-term rentals booked [through Airbnb’s service] in New York violate the law.”

The recent data release by Airbnb was meant to make good on a promise by the company in response to the Attorney General’s report to be “open and transparent,” and to underscore its contention that the vast majority of the users of its service do so in compliance with state and local laws.

From the start, the release of this data was viewed with skepticism by some journalists, activists, and others that closely watch the “sharing economy.” In order to view it, interested parties needed to make an appointment to review the data in person at Civic Hall, where Airbnb is an organizational member. The data was highly redacted, was not published to company’s data website, and those viewing it were not allowed to copy it to review it more closely after their scheduled appointment.

In the weeks that followed the release, outside reviews of the data seem to contradict Airbnb’s primary claim that most of its hosts are using the service lawfully. Others have cited the need for more detailed information to draw definitive conclusions. Though Airbnb has indicated that it would like to share similar data on usage for other cities, there is no indication that the company will release more detailed information for New York City.

It seems clear that the ultimate question of whether Airbnb’s service is being used lawfully will be determined by examining data on how people use the service. State regulators and others know this and have used legal and other means to try and get this data. Airbnb also knows this, and it has carefully constructed its limited release of data (and its public outreach about this data release) to assert that they are in compliance with the law.

But if data is at the heart of government’s ability to regulate Airbnb and other “sharing economy” companies, why are they so ill-equipped to obtain and use it?

REGULATING THE SHARING ECONOMY

At its core, the sharing economy—whether defined by the example of Uber, Airbnb, or one of the other standard-bearers of this emerging class of business—represents a change in the way that people consume goods and services that is enabled by advances in technology. This change in consumption results in a challenge to an existing, entrenched market actor (for Uber, the taxi industry; for Airbnb, the hotel industry) that is subject to existing government taxes and regulations.

The challenge for public officials and regulators is to avoid stifling new innovation that can result in better services but at the same time to ensure the fair and equitable application of rules that have been set up to regulate business operations and protect consumers. This is an issue that can have significant political implications. Striking the proper balance between competing needs can indeed be tricky.

But this challenge is not a new one for governments—tension between regulators and private interests spans the history of collective governance.

Supporters of the sharing economy commonly criticize existing government regulations as outdated and ill-suited to support innovation by 21st century technology companies. Reputation systems are often pointed to as a 21st century alternative to traditional government regulation, to ensure that sharing economy firms and similar types of companies act in the best interest of consumers.

But there are a number of common examples where consumers engage in transactions for which they have an abundance of reputational information where the company providing the services is also highly regulated by government. Consider the example of dining out at a restaurant—never before have consumers had as much information as we do now about the quality and cleanliness of food service establishments. And yet, restaurants and food service establishments are highly regulated by multiple levels of government.

In addition, recent research specifically examining reputation systems used by technology companies suggests that reputation systems and more traditional central regulation can work beneficially in tandem. A recent study from the Ohio State University examined the reputation system used by eBay in conjunction with a buyer protection program—a centrally managed program to provide protections to buyers and recourse if they are dissatisfied with purchases (an approach strikingly similar to the notion of centralized regulation). The study concluded that:

“[W]e estimate that the total welfare rises by 2.9% after the introduction of the buyer protection program. This increased welfare demonstrates an efficiency gain by having the two mechanisms, the eBay Buyer Protection and eBay Top-Rated Sellers, in place.” [Emphasis added]

Sharing economy supporters also claim the the growth of companies like Airbnb, Uber, Taskrabbit and others has led to a fundamental change in the economy, with more people opting to become freelancers who—to paraphrase the words of sharing economy companies—become masters of their own destiny. But another recent study from George Mason University suggests that the freelancer phenomenon began long before the advent of sharing economy companies like Airbnb and Uber:

“Our data support the claim that there has been an increase in nontraditional employment, but the data refute the idea that this increase is caused by the sharing-economy firms that have arisen since 2008. Instead, we view the rise of sharing-economy firms as a response to a stagnant traditional labor sector and a product of the growing independent workforce.”

The George Mason study helps to clarify the role that sharing economy companies can play in a changing economy—as opportunities for traditional employment become scarcer, the sharing economy may play an important role in providing employment for a changing workforce.

But we should not allow these potential benefits to be offset by other negative consequences that may arise if sensible regulations are not applied sharing economy companies.

INFORMATION ASYMMETRY

The exercise of regulating private interests by government almost always involves an information asymmetry. Governments seek to discover the occurrence of specific activities that are subject to regulation and to apply relevant rules and taxes to those activities.

Prior to the digital age, governments sought to (and still seek to) address this asymmetry by hiring groups of trained employees like auditors, inspectors and agents. The job of these individuals is to investigate certain kinds of activities and transactions to determine if the activity in question falls under the authority of a specific regulation or regulating entity, and then to enforce any applicable rules or taxes.

With the rise of the internet and the dawn of the digital age, governments have employed a wide range of new tools to help ensure that the activities of private interests comply with rules that have been adopted by elected and appointed bodies. The steady march of technical advancement has also made compliance with government mandated taxes and rules easier and more efficient for businesses than ever before.

The tension between how technology alters production and consumption patterns, and how these new patterns square with existing government rules is not new.

In the 1960’s, the rise of mail order retailers began a protracted debate on the application of state and local sales taxes to remote sales—a debate that has raged through the time when internet retailers like Amazon developed and flourished, and that still rages today.

In the early 2000’s, a new class of business—bolstered by the increasing availability of broadband internet access—began to offer consumers new options for telecommunication services that bypassed the Publicly Switched Telephone Network. In a scenario that is remarkably similar to the sharing economy, these new VoIP companies competed against large entrenched industry incumbents that were heavily regulated by government by offering customers improved service, a better customer experience, and lower prices.

The tension between the new service being offered to consumers VoIP companies and existing government rules was ultimately resolved by an order from the FCC.

So while the tension with existing tax and regulatory requirements created by technical advances is not new, and existing government institutions have shown they are capable of resolving these tension to the benefit of consumers, things are a little different when we consider the companies that make up the sharing economy.

Sharing economy companies self identify as “technology companies”—not dispatch companies (in the case of Uber) or hoteliers (in the case of Airbnb) that happen to make heavy use of internet technologies. They position themselves not as providers of a service, but as enablers or connectors that bring together individuals that want to transact with each other.

The issue with respect to government regulations as they relate to sharing economy companies is not so much that existing regulations are outdated as some have claimed. Instead, it is that the infrastructure for ensuring compliance with these regulations was not constructed for the 21st century—or, at best, the infrastructure has been minimally and very unevenly built.

Government regulations need to speak the native language of these companies—in the 21st century, this language is almost always data in JSON or CSV format delivered over HTTP.

A NEW INFRASTRUCTURE FOR REGULATION

Consider Airbnb’s recent data release—what if the State of New York, as part of its request to the company to share data, had offered Airbnb the ability to publish data to its open data portal?

The state could have provided the company with a user account and requested that they publish their data using that account at regular intervals to allow for scrutiny by regulators and other interested parties. They could have provided Airbnb with existing guidelines for ensuring privacy as well as metadata guidelines to help ensure data quality.

Even if Airbnb didn’t opt to publish data to the state’s open data portal, the request to do so would have helped to better qualify the deficiencies in the data the company actually did release. The state’s portal already contains scores of data sets with detailed information from dozens of agencies. Are technology companies like Airbnb less equipped to publish data on their core business operations than the State Liquor Authority? Really?

With very few exceptions, government open data portals are one-way vehicles—transporting data unidirectionally from government agencies to external consumers. Governments largely don’t view their open data portals as platforms for comingling data from different data producers, much less as vital instruments for successful 21st century regulation.

But what if they did?

With complete enough data, the question of whether an Airbnb host is in compliance with the law is fairly easy to spot. The issue is that in the absence of a standard mechanism for sharing this data openly, companies like Airbnb can define their own terms for behaving in an “open and transparent” way.

We need to expand the way we think about open data so that it’s not just about agencies publishing data to an open data portal, but instead is an integral way that we collectively help ensure the health and stability of our communities. We need to expand our notion of “government as a platform” to go beyond just building new civic apps to helping ensure efficient compliance with rules that are adopted collectively through democratic processes.

We’ve started to assemble some of the building blocks for this new infrastructure, but we now need to put the pieces in place.

For example, some governments publish data on zoning rules as open data. But we need to go beyond simply publishing this data and expose these rules through an interface that allow them to be encapsulated in a transaction. This work has only just begun and is,for now,largely driven by actors outside of government.

Imagine an infrastructure that would allow companies like Airbnb to instantly determine if a potential short-term rental was authorized under local zoning and rental regulations, and to determine if a rental tax was due on the transaction and the amount.

We are woefully short of this goal.

In fact, in jurisdictions that specifically require short-term renters to register with the local government, there is no interface that supports an automated check to determine if a specific property has a permit and is authorized to conduct such a rental. The absence of this essential infrastructure to enforce local regulations may go a long way toward explaining the dismal rate of compliance.

It seems clear that governments will not be able to successfully regulate these new companies without the infrastructure necessary to do so.

Building the infrastructure for 21st century regulation will require us to expand our ideas of open data and government as a platform. Checking for compliance with tax and regulatory requirements—by either party in a sharing economy transaction—should be as simple as making an API call.

Constructing this infrastructure won’t be done overnight, and it probably won’t be inexpensive. But the stakes for state and local governments have never been higher.